Troubled Waters: The Legal and Humanitarian Consequences of India’s Suspension of the Indus Water Treaty

Troubled Waters: The Legal and Humanitarian Consequences

of India’s Suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty

By Muhammad Zaman Khan

When history looks back at 2025, it may mark it not only as a year of deepened hostilities between India and Pakistan but also as a turning point in the modern history of international law. In April, after a deadly terrorist attack in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir, attributed to militants allegedly operating from Pakistani soil[1] (A claim which has not been substantiated by any credible evidence whatsoever), India announced the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT)[2], a pact widely regarded as one of the most resilient and successful international treaties of the twentieth century. This decision, though couched in the language of national security, represents a seismic breach[3] in the foundational principles of international law: particularly the sanctity of treaties, the peaceful settlement of disputes, and the cooperative management of shared natural resources. The suspension of the IWT was not merely a bilateral act between two rival states; it was a rupture of the very idea that law can be a shield against violence and that agreements can endure beyond the vagaries of politics.

Although India has not formally declared the termination of the Indus Waters Treaty, it has instead held the Treaty in “Abeyance”. Abeyance under International Law can be best described as a political twilight, where obligations linger but are deliberately left unperformed. Yet in the world of international law, abeyance is an elusive, almost phantom category. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, the central text governing treaty obligations, speaks only of suspension and termination under strict conditions outlined in Articles 60 to 62[4]. It knows no language of abeyance. Likewise, the International Court of Justice, in its landmark ruling in the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project[5], made clear that the suspension of treaty duties must comply with rigorous legal standards and cannot be achieved simply by a state’s declaration or political discontent. Scholars such as Anthony Aust[6] have noted that while diplomats occasionally speak of treaties being “held in abeyance,” this is a matter of political convenience, not legal doctrine. Under the law, obligations persist until lawfully extinguished. The International Law Commission’s Articles on State Responsibility [7]only reinforce this view, stressing that states must either fulfill their obligations or invoke a lawful excuse recognised by international law; there is no middle ground. In this light, the distinction between abeyance and suspension collapses: absent a formal, justified suspension, the withholding of performance remains an unlawful breach. For these reasons, and to preserve legal clarity, this analysis will continue to refer to India’s actions as a suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty, a suspension that carries serious consequences both for Pakistan and for the broader fabric of international law.

This article seeks to critically explore the legal implications of India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty. It argues that India’s actions constitute a clear violation of binding international obligations, both under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969)[8] and the evolving corpus of customary international law regarding transboundary watercourses. It further examines the immediate and long-term humanitarian consequences of this decision for Pakistan, a state heavily dependent on the Indus basin for its survival. Finally, the paper reflects on the broader impact of this precedent on international relations, questioning whether any treaty can be considered safe in a world where strategic retaliation is increasingly prioritsed over legal fidelity.

The Indus Waters Treaty: A Foundation of Fragile Stability

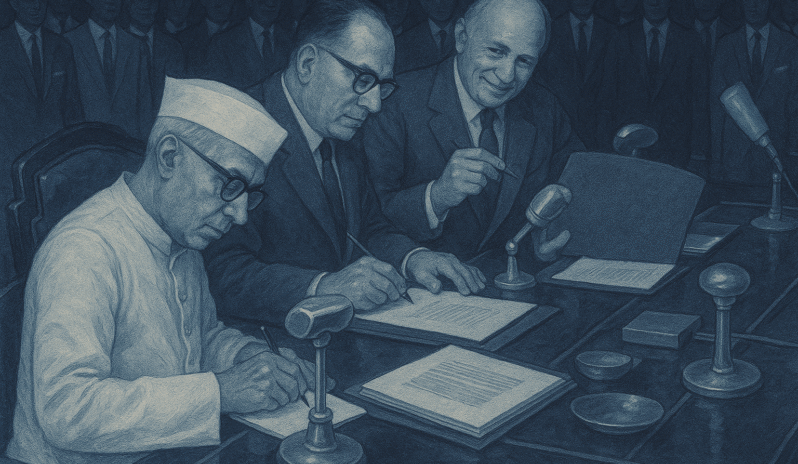

Signed in 1960 with the facilitation of the World Bank, the Indus Waters Treaty stands as a remarkable feat of diplomacy. In the aftermath of the bitter partition of British India and the first Indo-Pakistani War (1947–1948), sharing the waters of the Indus system posed not just a technical challenge but an existential one. The rivers of the Indus basin, after all, were, and remain, the arteries of life across the dry plains of Pakistan and the fertile fields of northwestern India. The Treaty divided the six rivers of the basin between the two countries: the three eastern rivers (the Ravi, the Beas, and the Sutlej) were allocated to India, while the three western rivers (the Indus, the Jhelum, and the Chenab) were reserved for Pakistan, albeit with limited Indian usage rights. This division was not simply political; it was a lifeline for Pakistan, whose agricultural economy depended almost entirely on the predictable flow of the western rivers.

Crucially, the IWT built a durable legal architecture to manage disputes. It created a Permanent Indus Commission, mandated annual meetings and data sharing, and offered structured pathways for escalation: technical disagreements could be referred to a Neutral Expert, while more serious disputes could be brought before an international Court of Arbitration. Importantly, the Treaty contained no provision for unilateral suspension or termination. Article XII explicitly required that any modification or termination of the Treaty must be achieved through mutual consent. In its design, the IWT reflected a deep understanding that when it comes to transboundary resources, unilateralism is a recipe for disaster.

The Treaty’s durability over sixty-five years was not coincidental. It survived three wars (1965, 1971, 1999), numerous skirmishes, and several rounds of diplomatic breakdowns. Even at the height of mutual distrust, water continued to flow across the Radcliffe Line. In an era where treaties often proved ephemeral, the IWT became a rare beacon of faith in the possibility of legal order amidst geopolitical chaos.

The Suspension of 2025: Context and Motivations

India’s announcement in April 2025 that it would suspend its participation in the IWT came as a shock, not only to Pakistan but to observers worldwide. The Pahalgam attack, horrific in its human toll, naturally prompted outrage in India, where public pressure for strong retaliatory action mounted rapidly. Within days, the Indian government announced the suspension of all dialogue under the Treaty and an immediate halt to the Permanent Indus Commission’s activities[9]. While India stopped short of explicitly announcing the complete abrogation of the Treaty, its statements indicated an intention to unilaterally “reconsider” the sharing of waters pending a “new security assessment.”

From a political standpoint, India’s move is not difficult to understand. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government, facing domestic calls for a firm response and emboldened by growing Anti-Pakistan Hindutva Narrative, viewed the Treaty’s suspension as a potent form of non-military retaliation, a retaliation against another country devoid of any evidence. This might just be the most loosely crafted narrative or accusation against a rival state. Water, after all, is a resource far more essential than territory or rhetoric. However, understanding the political motivations behind India’s decision does not legitimise it legally. Indeed, when viewed through the prism of international law, the suspension emerges as deeply problematic.

Breach of Treaty Obligations: Pacta Sunt Servanda and the Vienna Convention

At the heart of international treaty law lies the principle of pacta sunt servanda, the idea that agreements must be honoured. Enshrined in Article 26[10] of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, pacta sunt servanda provides that every treaty in force is binding upon the parties and must be performed by them in good faith. The unilateral suspension[11] of obligations under a treaty, particularly in the absence of a recognised legal justification, is a direct violation of this foundational norm.

Moreover, the Vienna Convention outlines the very narrow grounds under which a treaty can be suspended or terminated. Under Article 60, a material breach by one party can justify suspension by the other. However, the breach must relate specifically to the terms of the treaty itself. Pakistan has not been accused of violating its obligations under the IWT. The allegations concern support for terrorism, a grave issue in itself (devoid of evidence) but legally separate from the performance of the water-sharing regime. To allow suspension based on unrelated grievances would effectively render all treaties meaningless, permitting states to invoke any dispute as grounds for abandoning their legal commitments.

India might theoretically attempt to invoke the doctrine of rebus sic stantibus, a fundamental change of circumstances, under Article 62 of the Vienna Convention, the principle that a fundamental change of circumstances can sometimes justify treaty suspension or termination. Yet this doctrine, codified in Article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, is among the most narrowly construed exceptions in international law. However, as the International Court of Justice made clear in the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project (Hungary/Slovakia) case, the threshold for applying rebus sic stantibus is extremely high. The change must be unforeseeable[12], must affect essential bases of consent, and must radically transform the extent of obligations. Terrorist attacks, tragically, are neither unforeseeable in the India-Pakistan context nor do they affect the hydrological, environmental, or technical circumstances upon which the IWT was founded. In short, there is no credible legal pathway by which India’s suspension can be squared with its obligations under international treaty law.

Violation of Customary International Law on Shared Water Resources

Beyond the Indus Waters Treaty itself, India’s suspension also stands in stark violation of customary international law principles governing transboundary watercourses. Over the past century, a substantial body of international law has developed to regulate the use, management, and protection of shared rivers. These norms have been codified most notably in the 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses[13] (UN Watercourses Convention), but they also form part of general state practice and opinio juris even for states that are not parties to that Convention.

One of the most fundamental principles[14] in this area is the obligation of equitable and reasonable utilisation. States sharing an international watercourse must use it in a manner that is equitable and reasonable, taking into account the needs of other riparian states. Equitable utilisation is not merely a matter of fairness; it is a legal obligation designed to prevent conflict and ensure sustainability. The unilateral suspension of water-sharing dialogue, and the implied threat of altering water flows, is entirely antithetical to this principle. It seeks to weaponise water, turning a shared resource into a tool of coercion, contrary to the spirit and letter of international water law. Closely related to equitable utilisation is the obligation not to cause significant harm. This duty requires that states, in their use of shared water resources, avoid causing substantial injury to other riparian states. India’s actions, by jeopardising Pakistan’s access to water essential for drinking, farming, and energy generation, directly risk causing exactly such harm. Even if the Treaty were somehow invalidated, which it is not, India would still be bound by this customary duty[15]. The attempt to punish Pakistan by creating conditions of water scarcity flouts not only bilateral obligations but broader humanitarian imperatives recognised across the international community.

A third violated principle is the duty to cooperate. States are legally obligated to cooperate over shared resources, exchanging information, notifying one another of changes, and consulting in good faith before undertaking actions that could have transboundary impacts. India’s abrupt suspension of IWT mechanisms, without consultation, violates this duty. There was no prior warning to Pakistan, no offer of negotiation, and no attempt to mediate the underlying security concerns through existing or alternative frameworks. The move was unilateral in the purest and most dangerous sense of the term. Thus, even viewed independently of the IWT, India’s behavior falls foul of well-established international legal standards regulating shared water resources. The consequences of ignoring these norms go far beyond South Asia; they undermine fragile cooperative arrangements over rivers from the Nile to the Mekong to the Tigris-Euphrates.

The Humanitarian Fallout for Pakistan

The Indus River system is not merely an important resource for Pakistan; it is its existential lifeline. Nearly 90% of Pakistan’s agricultural production depends on irrigation from the Indus and its tributaries[16]. Major staple crops, wheat, rice, cotton, and sugarcane, are irrigated through canals and aquifers fed by the system. Already a water-stressed country, Pakistan faces a rapidly worsening crisis exacerbated by climate change, poor management, and population growth. The World Resources Institute has ranked Pakistan among the most water-stressed nations in the world, with a projected water deficit by 2025. In such a fragile context, any disruption to the Indus flows, even temporary, risks catastrophic humanitarian consequences.

If India were to alter flows on the Chenab or Jhelum rivers, whether by storing waters, diverting them for domestic use, or merely delaying releases, Pakistan’s agricultural heartlands in Punjab and Sindh could suffer immediate damage. Crops dependent on seasonal flooding and irrigation would fail. Food insecurity would soar. Already volatile rural regions could descend into instability. Mass internal displacement would be a real possibility, straining urban infrastructures that are already buckling under pressure. The spectre of widespread famine, once considered unthinkable in South Asia after the Green Revolution, would again haunt the region. Beyond agriculture, the suspension threatens Pakistan’s energy security. Approximately 30% of Pakistan’s electricity is generated through hydropower, largely from dams and barrages on the Indus system. Interruptions to river flows could force more reliance on expensive, carbon-intensive fossil fuels, deepening an economic crisis already fueled by inflation and external debt.

At a deeper level, the use of water as a political weapon cuts against fundamental human rights. Access to clean water is recognised under international law as a basic human right essential for the realisation of other rights[17], including the rights to life, health, and food. The United Nations General Assembly Resolution 64/292 (2010)[18] affirmed the human right to water and sanitation, underscoring states’ obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill access to water without discrimination. If India’s suspension results in deprivation of water for millions of Pakistanis, it would implicate not just state-to-state responsibilities but also broader human rights violations.

Legal Remedies Available to Pakistan

Faced with India’s unilateral suspension, Pakistan is not without legal recourse, although the available mechanisms are imperfect and fraught with political challenges. The first avenue is to invoke the dispute settlement mechanisms within the Treaty itself. Article IX of the IWT provides for settlement through negotiation, neutral expert determination, and, if necessary, adjudication by a Court of Arbitration. Pakistan could initiate proceedings on the grounds that India has violated its obligations under the Treaty by suspending dialogue and threatening to alter water flows[19].

In parallel, Pakistan could seek remedies under general international law. It could bring a case before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming breach of international legal obligations under the Vienna Convention and customary law principles. Pakistan would have to demonstrate that India’s actions have caused, or imminently threaten to cause, significant injury to Pakistan’s rights and interests. Although the ICJ’s jurisdiction would require India’s consent (which is unlikely), Pakistan could alternatively approach the UN Security Council[20], arguing that India’s actions threaten international peace and security under Chapter VI of the UN Charter. Furthermore, Pakistan could rally international support through diplomatic forums. By emphasising the humanitarian dimensions of the crisis, the potential for mass hunger and displacement, Pakistan could appeal to international public opinion, framing the issue not simply as an Indo-Pakistani dispute but as a violation of global norms of treaty stability and human rights protection.

Reputational Costs and Strategic Risks for India

While India’s decision may yield short-term domestic political gains, it carries significant long-term risks to its international standing. India has painstakingly cultivated an image of a responsible rising power, a country committed to the rule of law, multilateralism, and dispute resolution. That image is badly tarnished when India itself appears to abandon legally binding commitments in favour of expedient retaliation.

This reputational cost could have concrete consequences. States considering trade or investment agreements with India may hesitate if India demonstrates a willingness to set aside binding obligations when politically convenient. Moreover, India’s position in global forums, from the United Nations Security Council to regional organisations like SAARC, could suffer. Critics will find it harder to accept Indian leadership in international law-related domains when India itself flouts core legal principles.

There are also strategic risks. The use of water as a tool of coercion sets a dangerous precedent that could be used against India in the future. China, which controls the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra River, could view India’s behaviour as license to alter flows unilaterally, justifying its own projects that threaten India’s northeastern states. By normalising the weaponisation of water, India may ultimately weaken its own defenses against future hydropolitical aggression.

The Global Consequences for International Treaty Stability

What is perhaps most alarming about India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty is not simply the bilateral implications for South Asia, but the profound threat it poses to the broader architecture of international treaty law. Treaties are the lifeblood of the international order. They underpin peace settlements, trade regimes, environmental protections, arms control agreements, and human rights compacts. If a state can unilaterally suspend its obligations under a valid treaty simply by citing security concerns, without clear legal justification, adjudication, or even negotiation, the entire edifice of treaty-based cooperation begins to crumble. The consequences would not be limited to water-sharing agreements[21]. If the norms governing the Indus Treaty are allowed to erode without accountability, what prevents states from similarly suspending their obligations under arms control treaties, disarmament agreements, border accords, or refugee conventions? The reverberations could be global and catastrophic. In a world already straining under the pressures of nationalism, climate change, and resource competition, the weakening of treaty sanctity would open the door to instability and opportunistic revisionism on an unprecedented scale.

International law, at its core, relies on the good faith of states[22]. Unlike domestic legal systems, there is no centralised global police force to enforce compliance; the system depends on a shared commitment to norms and mutual enforcement through diplomatic, economic, and reputational consequences. When a major state like India, the world’s largest democracy and an aspirant for greater global leadership, acts in a manner that undermines these norms, it sends a dangerous signal. If law is no longer binding when inconvenient, then the very concept of a rule-based international order collapses into naked power politics.

Moreover, India’s actions undercut decades of effort to create specialised legal regimes for transboundary resource management. From the Nile Basin Initiative in Africa to the Mekong River Commission in Southeast Asia, fragile river-sharing arrangements rely heavily on trust and adherence to established agreements. The precedent that a state can abandon such agreements in times of political tension without even attempting renegotiation or mediation could embolden similar behaviour elsewhere, potentially triggering a chain reaction of disputes over shared resources. In this way, the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty is not merely a regional event; it is a moment of global significance. The international community, if it cares about the future of treaties, cannot afford to treat it with indifference.

Water as a Weapon: Ethical and Strategic Dimensions

The strategic logic behind India’s move is clear: by threatening Pakistan’s water security, India seeks to impose costs on its neighbour without resorting to direct military confrontation. However, the weaponisation of water raises profound ethical questions that transcend legal analysis. Water is not merely a strategic resource; it is the very basis of life. International humanitarian law, as reflected in the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions[23], prohibits the targeting of objects indispensable to the survival of civilian populations, including water installations, during armed conflict. While the Indus situation does not (yet) amount to an armed conflict in the technical sense, the underlying principle remains: denying access to water as a tool of political coercion is morally abhorrent. Moreover, using water as a weapon creates incentives for preemptive escalation. If Pakistan perceives that its survival is threatened by India’s actions, it may respond not merely with legal challenges but with military measures, including strikes against Indian infrastructure. Water wars, once a dystopian fantasy, become plausible scenarios when water security is deliberately undermined. The long-term strategic wisdom of weaponising water is thus deeply questionable. What may yield short-term tactical advantage risks sowing the seeds of future conflict on a vastly more destructive scale. Restraint, cooperation, and reaffirmation of legal commitments are not merely idealistic preferences; they are strategic necessities in a world where existential resources like water are increasingly scarce.

Toward a Legal and Moral Restoration

Faced with this profound challenge, what can be done to restore the primacy of law and cooperation over unilateralism and retaliation? First, India must be urged, through diplomatic, economic, and reputational pressure, to reverse its suspension and re-engage with the Indus Waters Treaty mechanisms. The Permanent Indus Commission must be reactivated, and dialogue on water management must resume independently of broader political disputes. Water cooperation cannot be held hostage to security concerns without risking disaster for millions of civilians. Second, the international community, including the United Nations, the World Bank (as a historical guarantor of the Treaty), and regional organisations, must take a more active role in mediating the dispute. The UN General Assembly could adopt resolutions reaffirming the importance of water-sharing agreements and condemning unilateral suspensions. The Security Council, though often paralysed by great power politics, should at least put the issue on its agenda as a matter affecting international peace and security.

Third, international legal bodies, including the International Court of Justice and the Permanent Court of Arbitration, should be ready to offer advisory opinions or adjudicatory processes if the parties consent. Even in the absence of binding judgments, authoritative legal analysis can help reassert the normative framework that treaties must be respected. Fourth, there is an urgent need to build greater resilience into international water law. Future treaties must include clearer enforcement mechanisms, third-party oversight, and binding dispute resolution clauses that limit states’ ability to suspend obligations unilaterally. Climate change, population growth, and political instability will make transboundary water conflicts more likely, not less. Legal architecture must evolve accordingly.

Finally, a deeper cultural shift is needed. Water must be treated not as a weapon, not as a bargaining chip, but as a shared heritage of humanity. Educational campaigns, civil society initiatives, and cross-border scientific cooperation can help build constituencies for peace even when political relations are strained. Law alone cannot guarantee stability; it must be buttressed by public awareness and political will.

Conclusion

The suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty by India in 2025 marks a dark chapter in the history of international law. It violates the binding obligations of treaty law, contravenes the principles of equitable and reasonable utilisation of shared resources, threatens to trigger humanitarian catastrophe in Pakistan, and undermines the broader stability of international agreements worldwide. It exemplifies how short-term political calculations can erode decades of painstaking legal and diplomatic achievement. Yet it is not too late to reverse course. The crisis surrounding the Indus Waters Treaty can serve as a wake-up call, a reminder that treaties are not mere scraps of paper but the fragile threads that hold our world together. Reaffirming the sanctity of treaties, strengthening international water law, and building deeper cultures of cooperation are not luxuries; they are imperatives for survival in an increasingly interconnected and precarious world. India, Pakistan, and the international community must act swiftly to mend the broken trust. The rivers must continue to flow, not just with water, but with the promise of peace, law, and shared humanity.

About The Author (For Editorial Use):

Muhammad Zaman Khan serves as the Director of the Centre for Law, Justice & Policy (CLJP) at Denning Law School, where he also teaches International Protection of Human Rights Law and Jurisprudence. He holds an LL.M. (Master of Laws) from Washington University in St. Louis (USA), With experience working at the intersection of International Law, policy, and education, Mr. Khan has worked on various projects with International Organisations such as the UN bodies and the ICRC (International Committee of The Red Cross), he has also mentored researchers and students across a wide range of prestigious academic and co-curricular platforms. His professional and academic endeavours are grounded in a commitment to advancing legal scholarship, fostering critical dialogue, and strengthening the role of law as a tool for justice and social change.

[1] India Suspends Indus Waters Treaty Talks with Pakistan after Kashmir Attack,” The Economic Times, April 2025.

[2] Indus Waters Treaty (1960), between the Governments of India and Pakistan, brokered by the World Bank

[3] See, e.g., Ian Sinclair, The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (2nd ed., 1984); Mark Villiger, Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (2009).

[4] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 23 May 1969, Articles 60–62.

[5] Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project (Hungary/Slovakia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1997, p. 7.

[6] Anthony Aust, Modern Treaty Law and Practice (3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 232–234.

[7] International Law Commission, Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, 2001.

[8] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 23 May 1969, United Nations Treaty Series, vol. 1155, p. 331.

[9] India Suspends Indus Waters Treaty Talks with Pakistan after Kashmir Attack,” The Economic Times, April 2025.

[10] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 23 May 1969, Art. 26.

[11] See Dapo Akande, “Treaty Breach and Suspension,” in The Oxford Guide to Treaties (Hollis, ed., 2012); Malcolm Shaw, International Law (9th ed., 2021) at 910-915.

[12] See James Crawford and Simon Olleson, “The Exception of Fundamental Change of Circumstances,” in The Law of Treaties Beyond the Vienna Convention (Enzo Cannizzaro ed., 2011).

[13] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, 21 May 1997.

[14] See Stephen McCaffrey, The Law of International Watercourses (2nd ed., 2007); Gabriel Eckstein, “The Development of International Water Law and the UN Watercourses Convention,” in International Water Law and Policy Series (2013).

[15] Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2010, p. 14.

[16] World Resources Institute, “Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas: Country Rankings,” 2024.

[17] See International Law Commission, Draft Articles on the Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities(2001).

[18] United Nations General Assembly Resolution 64/292, “The Human Right to Water and Sanitation,” adopted 28 July 2010.

[19] Indus Waters Treaty, Article IX.

[20] United Nations Charter, Chapter VI.

[21] Salman M.A. Salman, “The Indus Waters Treaty: Fifty Years Later,” Water International, Vol. 32, No. 2 (2007).

[22] See Martti Koskenniemi, The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870–1960 (2001).

[23] Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 (relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts), 8 June 1977.